The Grave and the Light

A Story of What Was Taken — and Given Back

I.

The bells had stopped ringing for the dead.

Once, the little hill above San Michele had chimed almost every week. You could hear it from the harbor and from the stony orange groves and from the cramped houses stacked like crockery along the lane. A death meant a Mass, and a Mass meant bells: bright, thin sound over dust and goats. But famine had a way of stopping certain things. Babies had stopped coming. Old people clung on with a desperate, wiry spite. The only ones who died now were the ones who worked too hard or stole from the wrong granary.

And when the bells fell quiet, nobody paid much attention to the hill.

Except for men like Carlo and Nunzio.

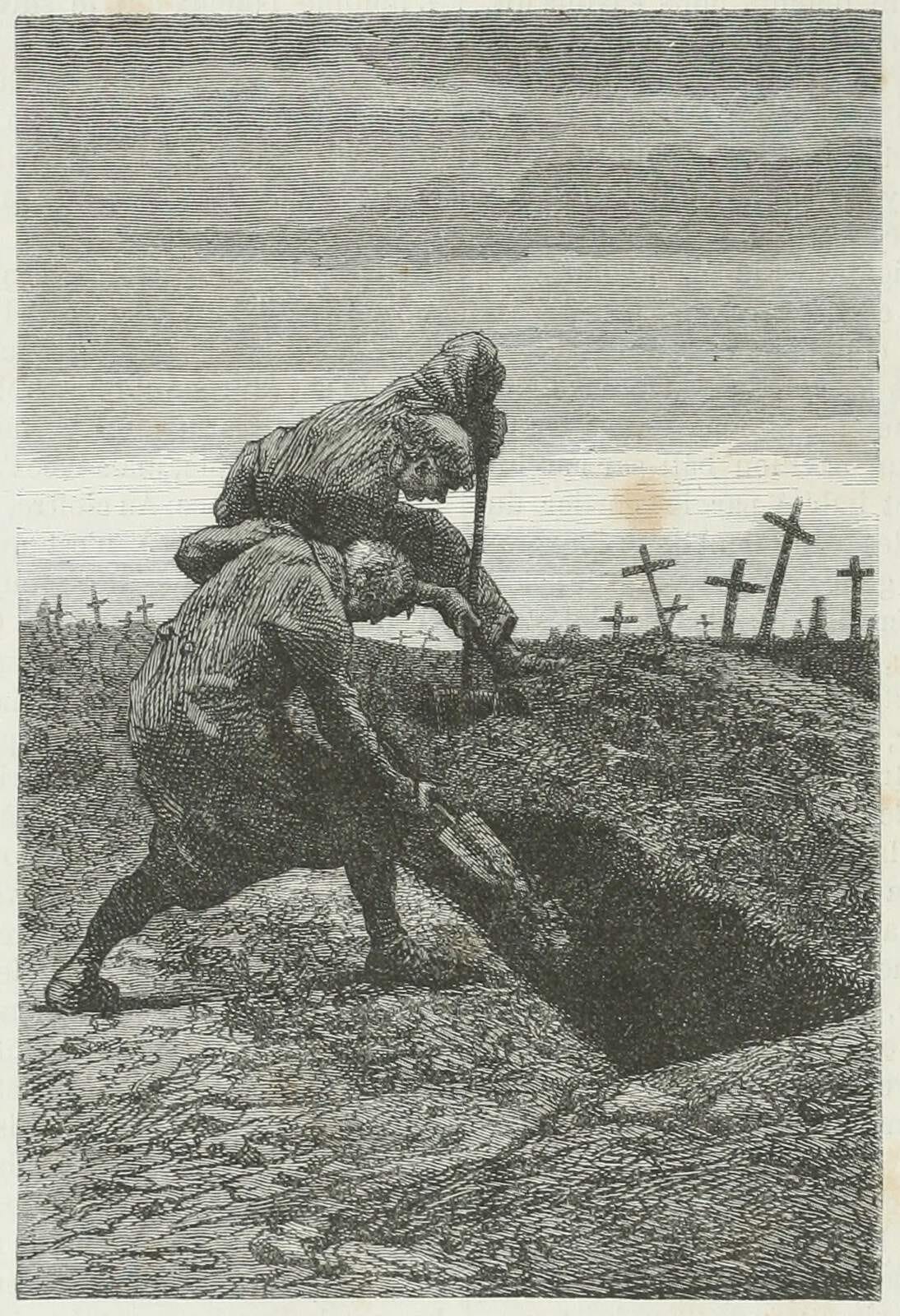

They came up under a sky the color of old iron, walking without lanterns, following the faint pale strip of the path where years of bare feet had worn the grass away. The wind smelled of salt and hearth smoke; down in the town someone was still baking bread with more sawdust than flour, and the ache of it sat in the throat like a memory.

Nunzio hunched in his patched cloak, fists jammed into his sleeves to hide their shaking.

“I do not like doing this at night,” he muttered.

Carlo, taller and heavier, didn’t bother to answer. He trudged ahead, boots grinding loose stone, shovel knocking against his shoulder at every step like a second heartbeat. His silhouette was all edges: hooked nose, jutting chin, shoulders thickened by years of hauling nets and sacks. Where Nunzio was all nerves and thin cheeks, Carlo moved with the stubbornness of a man who had once been strong for honest work and did not know what to do with that strength now.

“Carlo,” Nunzio tried again, a little louder. “Do you hear me? I said I do not like this.”

“Good,” Carlo said. “Only a fool likes robbing graves.”

He said it so flatly that it almost sounded like a joke. Nunzio offered up a weak laugh and fell into step beside him.

San Michele’s burying ground rose from the hillside like a scatter of broken teeth. Whitewashed tombs with iron crosses, low stone mounds with wooden markers already tilting, a few marble angels streaked with mildew and bird droppings. The oldest graves had no names left at all, only lichen and the memory of hands that had once pulled rocks into shape.

The little chapel squatted at the center, its plaster flaking like old scabs. A cracked fresco of Saint Michael glowered above the doorway, his paint-worn sword raised over a dragon that was mostly plaster now. The chapel door was bolted, but they had no reason to go inside. What they wanted lay in the yard.

Carlo stopped on the path and swept a slow look over the graveyard.

“There,” he said.

Nunzio squinted. “Why that one?”

The grave Carlo indicated was close to the low exterior wall, under a leaning cypress. It was marked by a plain stone slab with a cross carved shallowly into it, the grooves dark with trapped rainwater. No name, no date, no boast about the soul beneath.

“You see?” Carlo said. “No family comes to pray. No flowers. No candles. Nobody will notice if it settles a little more in the next weeks.”

Nunzio swallowed. His tongue tasted of metal. “And you’re sure the old woman said—”

“She said there was a holy man once,” Carlo cut in, impatient, “buried here by the brothers from the hermitage above the town. A miracle-worker. A black friar, she said, from the times when there were more monks than fishermen. And when they opened his grave for some reason—some dispute, who knows—they found him like he was sleeping. They took his bones to the big church in Palermo, but they left some little things. A belt. A rosary. The cloth that had touched his skin. You know how these things are.” He spat to one side, as if to show his contempt for relics, but the gesture was nervous. “People will pay for such things.”

Nunzio considered the stone again. “If they already took his bones…”

“Relics aren’t only bones,” Carlo said. “And in hard years, pious people pay more for saints than for bread. We are simply—” he glanced at the chapel, then dropped his voice in a parody of learned speech “—adjusting the balance of Providence.”

Nunzio made the sign of the cross anyway. “You talk like a lawyer.”

“I talk like a man who would like to eat,” Carlo replied.

The wind picked up, tugging at their cloaks. Somewhere down in the town a dog began to bark, then another, then many, until the hill seemed surrounded by small, distant anger. The first drops of rain tapped the stone like fingertips.

“Quickly,” Carlo said.

They set to work without ceremony. Carlo drove the shovel into the soil with the familiarity of a man who had dug more graves than he’d like to admit—some for work, some for less honest reasons. The earth was damp from the winter rains, dark and heavy. Nunzio knelt with a smaller spade, scraping the loosened clods away.

The sound of digging in a graveyard is always louder than it should be. Every clink of metal on stone rang out, seeming to wake the carved angels. The smell was an intimate, rich scent: roots and old water, the breath of things that had been soil for a long time.

“You’re sure this is the one,” Nunzio muttered. “The old woman, she could barely see. Do you remember her eyes? Like milk. She could have meant the grave over there.” He nodded at another unmarked mound.

Carlo did not pause. “She remembered the cypress. She said he was buried beneath the only cypress on the hill. How many do you see?”

Nunzio looked up. The cypress loomed above them, its needles swaying against the bruised sky like a black flame. “One,” he admitted.

“Then dig.”

They sank knee-deep into the pit before they hit the first stones. Carlo slowed, clearing the soil carefully around the bricks that lined the grave. Sweat slicked his neck. Rain began to patter more insistently, soaking fabric, turning the top layers of earth to a thin, clinging mud.

Nunzio’s teeth chattered. “We could still go back,” he said. “Steal chickens. A goat. Something that does not belong to God.”

Carlo snorted. “Chickens get you beaten. Saints get you paid and maybe forgiven, if you pray right.”

“You truly believe that?”

Carlo hesitated. For a moment his shovel rested across the bricks like a crossbeam.

“I truly believe,” he said slowly, “that I have seen men worse than us crawl into churches with their pockets full of stolen gold and crawl out again convinced God smiled on them. We, at least, are only looking for a scrap of cloth.”

He did not say what else he believed: that the God of the brothers in their whitewashed chapel had never once intervened when his own children coughed blood in a single winter and were buried in rough pits without stone or cross. There were some things you did not say aloud, even in the dark.

Beneath the bricks, something dull and pale showed through.

“Wood,” Carlo grunted. His heart gave an uncomfortable lurch.

He cleared more earth. There was indeed a wooden lid, narrow and long, the grain raised by age. A faint line of wax sealed the join between the planks and the stone border of the grave, gone brittle and crumbled in places. Even in the dimness, Nunzio could see something pressed into that wax: a seal, once clear, now blurred. A small cross, and around it what might have been letters.

“Wait,” Nunzio said, reaching out. His fingertips brushed the wax. There was a kind of stickiness still, after all these years, as if something of the intention that had sealed it lingered there. He felt a sting in his scalp. “This looks… different.”

Carlo’s mouth tightened. “It looks like every coffin the Church thinks is important. Which means we probably chose correctly.”

“We should not break a seal like that,” Nunzio whispered. “We should not.”

“Then go back down the hill,” Carlo said. “Go and starve politely. I won’t stop you.”

Nunzio stared down at the wood. The rain drummed on his shoulders, trickling cold between his shoulderblades. He thought of the cracked heel of bread on his mother’s table, of his younger sister’s wrists like twigs, of the way the baker looked at them now as if hounds had followed them inside.

He looked up at the chapel. No light showed through the narrow window slits.

“You said they took his bones already,” Nunzio murmured. “What harm to take what they left?”

Carlo said nothing. His fingers tightened around the shovel. It was a kind of answer.

They worked at the edges of the lid with the metal blades, prying, levering. The wood creaked softly, complaining in its long sleep. Nunzio expected a smell—sweet and terrible, the way they said old graves sometimes were—but only the wet earth breathed around them, steady and indifferent.

At last the lid gave with a rasp, one of the iron nails snapping. Carlo wedged his shoulder under the plank and heaved. The coffin cracked open.

They both leaned in, breath clouding in the cold air.

Inside, the saint lay as if he had stopped to rest between chores.

The body was clothed in a simple habit, a dark, coarse material like the Franciscan brothers wore down in the town. A rope belt knotted about the waist. The hands rested crossed over the chest, fingers wrapped lightly around a wooden cross worn smooth by touch. The face—

Nunzio’s stomach dropped. His first thought was that the man was only sleeping, that there had been a mistake. Dark brown skin, uncollapsed, the cheeks only slightly sunken. The eyelids shut gently, lashes still visible. A hint of beard along the jaw. Even the lips, though pale, had not blackened or shriveled. A few stray curls of black hair escaped the edge of the simple hood and lay along the forehead.

“Blessed Mother,” Nunzio whispered. “He… he is not…”

He reached down, hand trembling, to touch the cheek. The skin was cool. Not the slimy chill of rot, nor the waxiness of a carved effigy. Just… cool. The way a monk’s face is cool in the early morning before Lauds.

Carlo pulled him back by the wrist so sharply that Nunzio stumbled. His own heart had lurched into his throat. He had seen death many times, on boats and in alleys and on the plague cart when he was a boy. He had never seen this.

The smell reached them then: not corruption, but a faint, penetrating sweetness, like crushed bay leaves and something harder—myrrh, perhaps, or the scented oil the sacristan used at Easter. It slid through the wet, muddy air like a thread of light.

The wind dropped.

Not died down slowly, not shifted. Dropped. The rain, which a moment ago had been spitting and gusting, suddenly fell straight as strings, each drop gentle. The barking dogs in the town cut off mid-howl. A stillness spread up the hill, over tombs, over stone, over the two men, as if someone had cupped a hand over the whole world.

Nunzio looked up, startled. “Did you—”

“Quiet,” Carlo said, but his own voice was thin.

Something about the hands of the saint drew the eye. They were broad, calloused, the nails blunt and clean. Hands that had cooked and scrubbed and blessed. Around the knuckles, the faint shadows of once-healed burns. The fingers did not move, yet Nunzio could not shake the feeling they were about to.

“Maybe we should put it back,” he whispered hoarsely. “Seal it, fill the grave. We saw enough. We know he is holy. That should be enough.”

“And go home with what?” Carlo snapped, too loudly. His voice echoed off the chapel wall. He flinched. “With the story of what we did not take? Will that feed Lucia? Will that buy your sister medicine?”

He stared down at the corpse again. The eyes remained shut.

“It is only a belt,” Carlo said, more softly. “Perhaps his rosary. These are things, Nunzio. Wood and rope. If they were meant never to be touched again, God could have turned them to stone.”

He reached in, aiming for the rope belt, trying to keep his eyes on his own hands and not on the still face between them.

The smell of myrrh deepened.

There was a sound somewhere between a sigh and the soft release of a held breath.

Carlo’s fingers closed on the cord just as the saint opened his eyes.

They were dark, deep as wells, and they were entirely alive.

Carlo jerked back, but his hand was tangled in the cord. Nunzio yelped and fell onto his backside in the wet soil, scrabbling away until his shoulders hit the grave wall. The coffin creaked as the figure within it shifted.

The saint sat up.

He moved without the stiffness of long sleep, as if he had merely been lying down to rest and risen because someone had called him. His habit fell in simple folds about him. Earth clung to the edges, but not to his skin. When he unfolded his legs and swung his feet to the side, they rested firmly on the lower bricks of the grave. He was not imposing in height—about Carlo’s shoulder—but there was a solidity to him, like the trunk of an olive tree that has stood through many seasons.

His gaze moved from Carlo, who had frozen with his hand still half-wrapped in the rope belt, to Nunzio, who was trying and failing to make the sign of the cross without his fingers shaking, then up to the sky. The rain touched his face and beaded on his lashes, but he did not blink it away.

For a heartbeat, nobody spoke.

Then the saint looked back at them, and a faint sadness touched the corners of his mouth. Not disgust. Not wrath. The kind of grief a father feels when he recognizes his own sons in a crime.

“Sons,” he said.

The word was not loud, but it seemed to reach into the soles of their feet. His voice held a soft Sicilian lilt, the vowels round and warm. It was the voice of a cook calling brothers to table, of a man who had spent most of his life saying simple things that mattered.

“Sons, why have you opened what Heaven has shut?”

Carlo’s knees tried to fold. He resisted. Pride, or terror, or some mingling of both held him upright. His mouth worked. “We… we did not know,” he stammered. “We did not know you were—”

“A man,” the saint finished quietly. “You knew I was a man. You knew I was a brother like you. That is enough.”

Nunzio found his voice first. It came out high and thin.

“Are you… are you Saint Benedict?”

The saint’s brows lifted just slightly, as if the question amused him. “Once, they called me Benedetto,” he said. “Benedetto the Moor. Benedetto the cook. Benedetto, the servant of the servants of God. Now I am only what the Lord will me to be.”

He looked around the graveyard with a kind of gentle curiosity, breathing in the wet air, the scent of orange blossom drifting faintly up from the town. There was no astonishment in his face, no panic; only the calm of someone who had known stranger things than waking in his grave.

“You disturbed my rest,” he said, returning his gaze to them. “So perhaps the Lord has permitted that I disturb yours.”

The words were not a threat, but Nunzio felt them cut all the same. He pressed himself harder against the bricks, as if he could melt through them.

“We are sorry,” he blurted. “We are sorry, santo. We are hungry. There is no work. The nets come up empty, the land is dry, the lord raises the taxes. No one will spare us bread for prayers, but they will pay for a bone, for a thread that has touched a holy man. We thought—”

“That holiness could be sold?” Benedetto asked, gently.

Nunzio’s cheeks burned. “We thought… we thought perhaps you would not mind if some small thing that belonged to you helped keep us alive.”

Carlo shot him a sharp look, but the words were already out. He dragged his hand free from the rope and bowed his head, jaw clenched.

“If there is punishment,” he said hoarsely, “give it to me. It was my idea.”

Benedetto studied him.

In that gaze, Carlo felt something he had not felt in many years: seen. Completely and without hiding. All the little tricks by which he had excused himself in his own thoughts—I steal only what they can spare, I hurt only those who would hurt me, I do this because I must—fell away as if they were dried leaves burned by a slow flame.

He swallowed. His throat was dry.

“There will be punishment enough in the world without me adding more,” Benedetto said at last. “Listen.”

He raised a hand. Long, broad fingers, scarred by kitchen knives and hot pans. They did not glow. No fire leapt from them. But when he touched his own chest lightly, above where his heart lay, the air seemed to ring, very softly, like a spoon tapped against glass.

“Once,” he said, “men beat me in the street because of the color of my skin. Once, I was slave and servant, bought and sold while those who owned me sang hymns louder than the cries of those they bought. Once, I was mocked in my own brotherhood for being ignorant of letters, though I knew a different kind of wisdom. The world is full of injustice, figli miei. You do not sin because you suffer. You sin because in your suffering, you choose to turn your face from God, not toward Him.”

Nunzio stared. Carlo’s lips parted, but no sound came.

“You could have gone to the brothers,” Benedetto went on. “You could have gone to the poorhouse to share their crusts. You could have knocked on doors. You could have stolen bread and risked your own body. But instead you came here, to the bones of a man who has given everything already, and you said: let him pay for us once more.”

The words made Nunzio flinch as surely as if they had been blows.

Benedetto reached out. His palm rested for a moment on the edge of the coffin, fingers spread, as if feeling the wood, the stone, the earth. His eyes were soft.

“And yet,” he said, “you are here. You did not flee when I opened my eyes. You did not try to strike me down. That is something.”

Carlo gave a strangled laugh. “Strike you down? Santo, I cannot even stand upright.”

“Good,” Benedetto said mildly. “Pride is a stiff thing. It breaks easily. Better to bend.”

He extended his hand, first to Nunzio.

The younger man stared as the saint’s palm hovered in front of his face, calloused and simple. Not glowing. Not ringed with gold. Just a working man’s hand.

“Stand up,” Benedetto said quietly. “There is something you must see.”

Nunzio hesitated. Every story he had ever heard about saints and ghosts and restless souls tumbled through his head. Men who were dragged to Hell by roaring figures. Men who woke from visions half-mad. But there was nothing roaring here. Only a calm, implacable invitation, like the sea at dawn.

He put his hand in Benedetto’s.

It was warm.

Not chill, not burning. Warm, like the palm of a man who has been standing near a hearth. A shiver went through Nunzio’s arm, up into his chest. For a moment his vision blurred, as if tears had rushed to his eyes without his consent.

Benedetto turned that steady gaze on Carlo.

“And you?” he asked.

Carlo had been a fisherman long enough to know when there was no other way but forward. He clenched his jaw, stepped closer, and wrapped his rough fingers around the saint’s offered hand.

The instant both men were in his grasp, something changed.

The hill, the tombs, the cypress, the chapel—all of it seemed to grow thin, as if painted on oiled paper and held up to a flame. The patter of the rain faded until it was only a memory on their skin. The smell of earth and myrrh and hearth smoke blurred into a single, indescribable sweetness, sharp enough to sting.

Nunzio’s first instinct was to jerk back, but Benedetto’s grip was gentle and utterly firm. Not restraining; holding. Steadying.

“Do not fear,” the saint said. “I have walked through worse darkness than this with the Lord beside me. I will not let you fall.”

The darkness came not with a rush but with a soft folding, like a cloak pulled over their heads. For an instant, Carlo thought he saw, beyond the dissolving graves, something like a broad kitchen with many brothers sitting at a plain table, steam rising from bowls, laughter warm as bread. For an instant, Nunzio thought he heard his little sister’s voice as it had been before sickness thinned it, singing.

Then those impressions were gone.

The graveyard vanished.

The last thing they knew of the hill of San Michele was the feeling of the saint’s hands around theirs, and the quiet weight of his voice, saying:

“Come. Let us look at your lives together.”

And the world fell away.

II.

They did not fall.

That was the first strange mercy.

Carlo had expected the sensation of dropping — the stomach lurch, the blind panic — but instead it felt like walking into deep water, the kind that takes you slowly, step by step, until the ground no longer answers your feet. The darkness that wrapped them was not violent. It folded around them with the patience of cloth.

Then there was light.

Not the hard glare of the sun, nor the trembling shimmer of candle-flame, but a broad, steady brightness, like early morning when the world has not yet decided what it will become. Carlo blinked. His eyes stung. When his vision cleared, he found himself standing on dry ground.

Dry, cracked earth stretched around them, pale as bone. The air was hot and still, and the sky above was an empty white vault without cloud or bird. No sea breeze. No chapel bells. No rain.

Nunzio gasped softly.

They stood at the edge of a wide field, ringed by low stone walls. Beyond the walls, olive trees twisted out of the dust, their leaves dull and gray, as if coated in ash. At the center of the field rose a single structure: a long, low hall built of rough stone, its doors thrown open.

Benedetto stood between them, unchanged. His habit stirred slightly, though there was no wind. His face bore the same calm gravity, but his eyes were intent now, watchful.

“Where are we?” Nunzio asked.

“Where you have been,” Benedetto said. “And where you are still choosing to remain.”

He gestured toward the hall.

“Come.”

Inside, the air was cooler. The hall was filled with men.

They sat on low benches arranged in long rows, heads bowed, hands clasped or hanging limp at their sides. Dozens of them. All ages. Some wore the clothes of laborers, some the remnants of uniforms, some fine garments torn and stained. Their faces were thin, lined, exhausted. No one spoke.

Carlo felt an immediate, irrational shame, as though he had entered a place he did not deserve to see.

“Who are they?” he murmured.

Benedetto walked slowly along the aisle, his sandals making no sound on the stone. As he passed, some of the men lifted their heads. Their eyes were empty, unfocused, as though something essential had been mislaid.

“They are men who believed the world took something from them,” Benedetto said. “Men who believed that because they were wronged, they were therefore justified.”

Nunzio frowned. “That could be anyone.”

“Yes,” Benedetto replied gently.

He stopped beside one of the benches and placed a hand on the shoulder of a man slumped forward, elbows on his knees. At the touch, the man looked up.

Carlo sucked in a breath.

The face was his own.

Not exactly — this Carlo was older, heavier, his eyes more sunken, his beard gray and uneven — but there was no mistaking him. Same nose, same crooked line to the mouth. The man stared back at him without recognition, then dropped his gaze again.

Carlo felt the room tilt.

“That is not—” he began.

“That is what you are becoming,” Benedetto said. Not harshly. Factually.

The saint turned to Nunzio.

“And that one?”

Nunzio followed his gaze to a thin man hunched at the end of the row, fingers picking endlessly at a frayed sleeve. When he lifted his head, Nunzio saw his own sharp cheekbones, his anxious eyes magnified by age and disappointment.

Nunzio staggered back a step. “No. I am not like that.”

“Not yet,” Benedetto said.

The hall seemed to deepen, stretching farther than it had moments before. Carlo noticed now that there were no windows. No doors but the one they had entered.

“Why are they here?” Carlo asked hoarsely.

“Because they never learned to suffer without bitterness,” Benedetto said. “Because they never learned to offer their wounds to God. They carried them like weapons instead.”

Benedetto turned, facing both of them fully.

“You believe your hardship excuses you,” he said. “That because the world has been cruel, you are permitted to be cruel in return. But suffering does not make a man righteous. It only reveals what he serves.”

Nunzio’s throat tightened. “We were hungry.”

“I was hungry,” Benedetto said.

The words fell simply, without emphasis, and yet they struck like a bell.

“I was beaten. I was mocked. I was told I did not belong among learned men because I could not read as they did. I scrubbed pots while others prayed aloud. And still, I served. Not because I was strong, but because Christ had already carried more than I ever would.”

He gestured again, and the hall dissolved.

They stood now in a narrow village lane, hemmed in by stone houses. The smell of smoke and refuse pressed in. It was dusk. Somewhere nearby, a woman was coughing — a deep, rattling sound that scraped the ear raw.

Carlo recognized the place at once.

“My street,” he whispered.

They were standing just beyond the doorway of his own house — the house he had not entered in over a year. The door stood ajar. Inside, a small oil lamp burned low.

Benedetto did not move.

“Look,” he said.

Carlo stepped forward as if pulled by a rope. Through the doorway he saw a woman seated at the table, her back bent, her hair streaked with gray that had not been there when he last looked at her closely. Lucia. His wife. Her hands moved with slow care as she cut a crust of bread in half.

Across from her sat a girl of perhaps twelve. Their daughter.

The girl pushed her portion back across the table.

“You eat it,” she said.

Lucia shook her head. “You are growing.”

“I am not,” the girl insisted, anger flashing through the fatigue. “I am the same size as last year.”

Lucia smiled, tired and fond. She broke the bread again, giving her daughter the larger piece.

Outside, Carlo’s chest burned.

“I could not come home,” he said, not looking at Benedetto. “I had nothing to bring.”

“And so you brought nothing of yourself either,” Benedetto replied.

The scene shifted.

Carlo watched himself — younger, broader — standing in the same doorway months earlier, voice raised, pride wounded.

What do you want me to do? he had shouted. Pull bread out of the stones?

Lucia had not shouted back. She had only looked at him with a quiet fear that hurt worse than accusation.

“I will not watch you rot here,” he had said. “I will not be a useless mouth.”

And he had left.

Carlo turned away now, breath ragged. “I thought I was sparing them.”

“You spared your pride,” Benedetto said. “And called it sacrifice.”

The lane dissolved.

They stood now beside a low stone wall bordering a field. The earth beyond was dry, cracked. A thin boy knelt in the dirt, trying to coax something from the soil with bare hands.

Nunzio stiffened.

“That is my brother,” he said. “Before he died.”

The boy looked up — younger than Nunzio remembered, his face all angles and hope — and smiled.

Nunzio’s knees buckled. Benedetto’s hand was suddenly at his elbow, steadying him.

“I prayed,” Nunzio said, voice breaking. “I prayed every night. I begged God to spare him.”

“And when he did not,” Benedetto said, “you concluded that prayer was a lie.”

The scene shifted again.

Nunzio saw himself weeks later, standing outside the church while bells rang for another man’s funeral. He had turned away, fists clenched.

God listens to rich men, he had thought. God listens to monks. Not to boys in the dirt.

Nunzio covered his face.

“I stopped asking,” he whispered.

“And so you stopped listening,” Benedetto said.

Silence fell between them — not empty, but full, like the pause before a confession.

At last, Benedetto gestured, and the light changed.

They stood now on a long road stretching toward a distant rise. Three paths branched from it.

One descended into a crowded town, narrow streets twisting endlessly. Men moved there in tight circles, each carrying burdens that grew heavier with every step.

Another path climbed sharply into barren hills, solitary and cold. Figures trudged alone, heads down, refusing help, refusing rest.

The third path wound gently upward toward a cluster of low buildings nestled among olive trees. Smoke rose there, thin and steady. Bells rang — not loudly, but regularly.

Benedetto faced them.

“These are the roads before you,” he said. “None are free of suffering. But only one leads you out of yourselves.”

Carlo stared at the monastery on the hill. “What if we fail?”

“You will,” Benedetto said, without cruelty. “And you will rise again.”

Nunzio wiped his face. “And if we do not choose it?”

Benedetto’s gaze softened, but did not waver.

“Then one day you will sit in the hall you saw first,” he said, “and wonder when your life became a waiting room.”

The road, the hills, the town — all faded.

The weight of rain returned. The smell of wet earth. Stone beneath their feet.

They were back in the graveyard.

Benedetto stood once more beside his open coffin, the rain falling around him now as it had before, though neither Carlo nor Nunzio could say when it had begun again.

“Your lives are still your own,” the saint said. “I will not walk the rest of the road for you.”

Carlo knelt without thinking. Nunzio followed.

“We will put you back,” Carlo said, voice thick. “We will seal the grave. We will tell no one.”

Benedetto smiled — not triumphantly, but with a deep, quiet relief.

“Good,” he said. “But that is not all.”

He gestured toward the earth beside the grave.

“There is still the matter of what you came here to take,” he said. “And what you must now return.”

The rain fell steadily.

The night held its breath.

And the final choice waited.

III.

They worked in silence.

The rain had softened the soil, and the earth yielded now without resistance, as if it had been waiting. Carlo laid the coffin lid back in place with careful hands, aligning the cracked edge, fitting the wood as best he could. Nunzio pressed the wax seal back into its groove, though it crumbled beneath his fingers. He whispered an apology for that too.

Benedetto had returned to his rest without ceremony. He lay once more with his hands folded, the wooden cross against his chest, eyes closed in the same gentle expression they had found there first. If anything, he looked more at peace now, as though the disturbance had been a necessary turning, not an offense.

Before they closed the grave, Benedetto spoke one final time.

“Men think holiness is something taken,” he said softly. “It is not. It is something received, and then given away.”

Carlo bowed his head. “We have nothing worthy to give.”

Benedetto’s lips curved in the smallest smile. “Then give what you have.”

They filled the grave slowly, tamping the soil down, setting the stone back in place beneath the cypress. When it was done, the rain slackened, then stopped entirely. A faint glow lingered over the earth — not a light you could point to, but a feeling, like warmth left behind after a fire.

Neither man spoke of miracles. They did not need to.

They knelt there, two muddy figures in the dark, and prayed as men pray when they have no eloquence left — with breath, with shame, with hope.

When they rose, the hill of San Michele was as it had always been. Cracked tombs. Leaning crosses. The chapel’s faded saint still glowering over the door.

Only the cypress seemed to stand straighter.

They parted at the foot of the hill.

Nunzio went toward the town, toward the monastery above the olive groves. He did not know what words he would use, only that he would knock. That would be enough.

Carlo went the other way.

He reached his street at dawn. Smoke curled thinly from the chimneys. When he pushed open his own door, Lucia looked up from the table and froze.

He did not speak at first. He simply knelt and pressed his forehead to the floor.

“I am home,” he said. “If you will have me.”

She crossed the room and placed her hand on his shoulder. She did not forgive him all at once. She did not need to. He would earn that, day by day.

Life did not become easy.

Nunzio scrubbed floors and hauled water for the brothers. He learned the rhythm of the bells, the steadiness of meals shared in silence. At night, he dreamed less of graves and more of fields that waited patiently for seed.

Carlo worked where he could. He mended nets, carried stone, returned what he could remember stealing. Sometimes doors closed in his face. Sometimes they did not.

Years passed.

The grave on the hill was never marked. No marble was set there. No reliquary raised. And yet people began to come.

A woman whose child had fever knelt there once and left bread behind. A fisherman touched the stone before putting out to sea. A monk from Palermo paused there, frowning, and later wrote a letter he did not explain.

On certain nights, villagers swore they saw two candles burning before the cypress, though no wax ever dripped, and no hand was ever seen to light them.

Carlo and Nunzio never spoke of the saint again.

But when they passed that hill, each made the sign of the cross — not in fear, not in debt — but in gratitude.

Because some men dig in the dark and find only bone.

And some are given back their lives.

This was a nice read. I think there were some really strong elements here. I can see this being perfect for a play or an episode in a short anthology on tv. Its good work, keep at it.

Hi Levi, I am a reader on this platform and look forward to your work given the tone of your opening section.

I have shared this with family and friends that I think will appreciate your talent.

I am not a Luddite but I don’t use my phone for $$. I know that must seem odd in this day and age—Still often with tech,better safe than…

But I will do so when I am back on my Mac. I hope that will be sufficient.

Stay the course! God Speed.